-40%

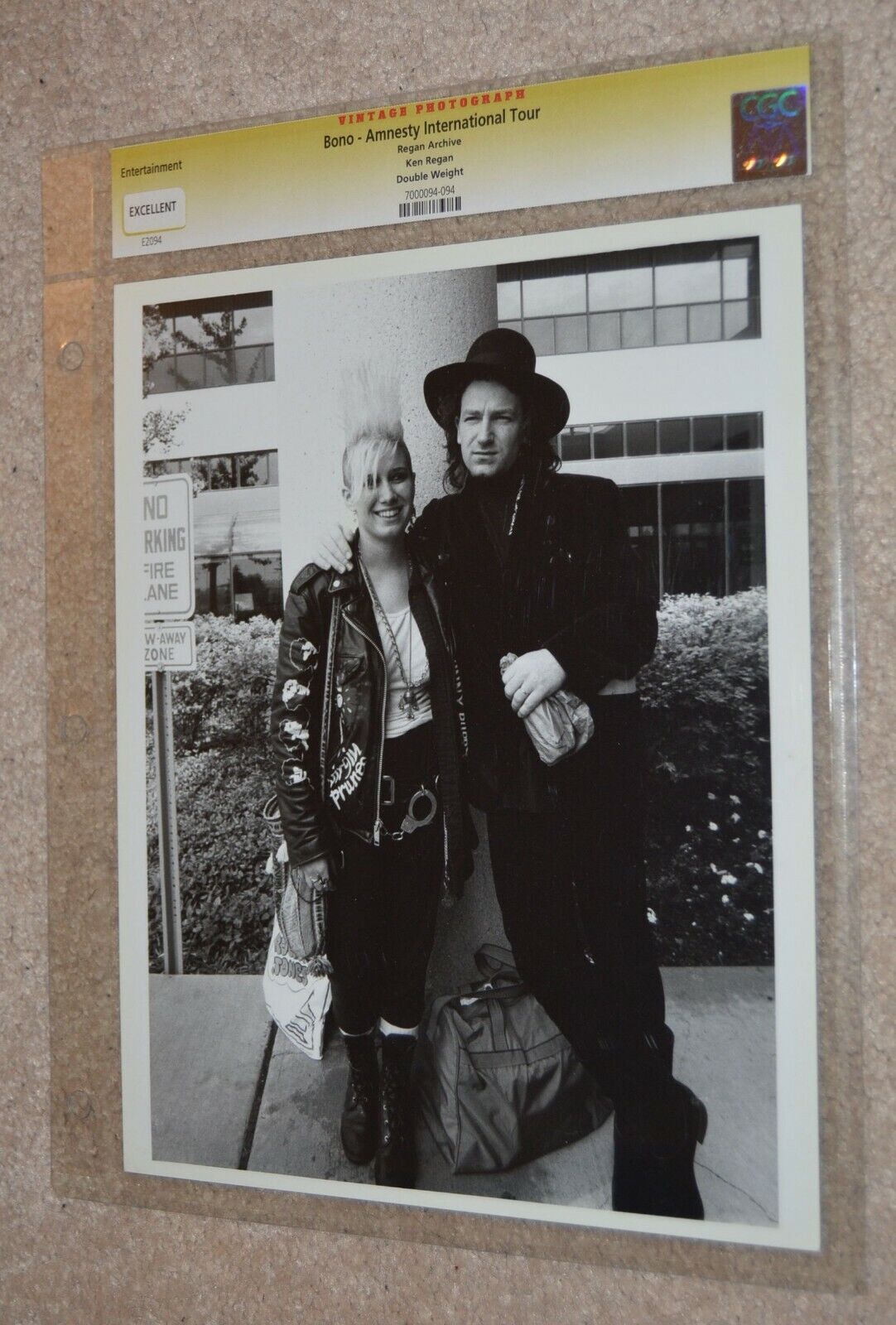

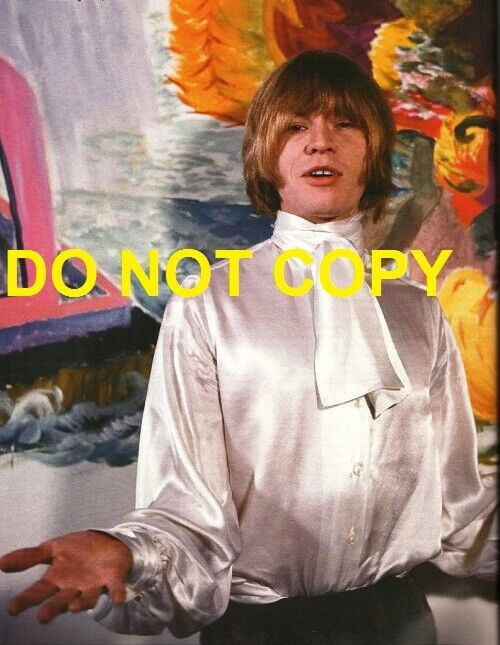

1986 BONO U2 KEN REGAN PHOTOGRAPHER 8X10 VINTAGE

$ 277.04

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

A FANTASTIC 8X10 INCH PHOTO OF BONO FROM U2 BY FAMED PHOTOGRAPHER KEN REGANKen Regan developed a passion for photography at a very young age. Raised in the Bronx, his world was New York City and it was in New York City that he would cut his teeth as a photojournalist. From the New York Yankees to the Fillmore East, Ken’s pictures told the story of a city during a time of transition, while they told his own story as well. Ken’s unparalleled knack for capturing a moment quickly paved his way to becoming a respected member of the press community. No story was ever out of reach for him to cover. He could walk into an event without a press pass, and walk out with the next cover of Newsweek or Time.

Ken Regan

Ken Regan developed a passion for photography at a very young age. Raised in the Bronx, his world was New York City and it was in New York City that he would cut his teeth as a photojournalist. From the New York Yankees to the Fillmore East, Ken’s pictures told the story of a city during a time of transition, while they told his own story as well. Ken’s unparalleled knack for capturing a moment quickly paved his way to becoming a respected member of the press community. No story was ever out of reach for him to cover. He could walk into an event without a press pass, and walk out with the next cover of Newsweek or Time.

Ken’s career took a path that defied labeling. With such a wide array of assignments thrown his way throughout the 1960’s, Ken learned how to artfully cut to the heart of anything that crossed his lens. He wasn’t specifically a sports photographer, a music photographer, a fashion, or landscape photographer. Ken was a photographer.

Ken’s work has appeared in countless magazines over his vast career, including such esteemed publications as Time Magazine, Sports Illustrated, Rolling Stone, People, Newsweek and Entertainment Weekly, among many others. He’s garnered numerous awards for his work. In the 1970’s, Rolling Stone named Ken as one of their Seven Masters of Photography. Ken’s work has also been exhibited in galleries all over the globe. He’s an author of many books, including such highly regarded titles as Knockout: The Art Of Boxing and All Access: The Rock N’ Roll Photography Of Ken Regan.

Ken Regan (June 15, c. 1940s – November 25, 2012) was an American photojournalist from the Bronx, New York City whose reputation for discretion allowed him close connections with subjects including many musicians, politicians and celebrities. He was the official photographer for the Rolling Stones on several tours in the 1970s. He also was the photojournalist on Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue tour in 1975 and the Live Aid concert in 1985.[1][2]

Regan was the unofficial personal photographer of Senator Ted Kennedy in the last four decades of Kennedy's life. Regan documented Christopher Reeve’s homecoming from rehabilitation after Reeve's 1995 horse accident which left the actor paralyzed. He photographed local politicians including Meade Esposito.[2]

Regan worked with Palace Press Inside Editions on a book called Knockout: The Art of Boxing.[3]

He was described by his colleagues as "a big deal".[4] Regan died of cancer in 2012. A spokesperson from his studio declined to release his age calling him "ageless".[5]

Ken Regan has been taking photographs professionally for more than 40 years. Movie icons. The Olympics. Foreign conflicts. Ballplayers. Politicians. And rock stars. His new book, All Access: The Rock ’n’ Roll Photography of Ken Regan is an exhaustive, gorgeously composed inside look at some of rock ’n’ roll’s most famous and famously private artists in intimate and outrageous settings. We talked with the New York native about how he got his start, some of his most indelible images, and that time Alice Cooper sat on Santa Claus’s lap.

GQ: Where did the idea for this book come from?

Ken Regan: Basically, Palace Press Inside Editions, a small publishing company in San Francisco, I did a book with them a couple years ago called Knockout: The Art of Boxing. I’ve done seven or eight books and they did such a beautiful job, and they were anxious after Knockout was out, to do another book with me. They suggested music because I have such a history in music and rock ’n’ roll over the last four decades, so that’s how it came about.

GQ: The access and creativity you have here is amazing. How’d you get your start shooting music?

WATCH

10 Things 2 Chainz Can't Live Without

Ken Regan: I started out very early, at 13 or 14, and I really was wanting to be a photographer and willing and ready to do anything I could to make that happen. I had a love for sports because I was an athlete in school and I also had a love for music. I started doing sports photography and started going to the Fillmore East, which was the place for musicians, a place in the East Village run by Bill Graham, whose name you may or may not know. He was kind of the P.T. Barnum of rock producers in the ’60s, ’70s, right up until the time he died in a helicopter crash in the ’90s. I would, from experience going to the Fillmore on my own without a camera or anything, I’d see the musicians and try to take some photographs. I’d take a camera in under my coat, ’cause there were signs for no photographs, and every time I went in there, Bill Graham would catch me and throw me out. It happened half a dozen times. I started showing my music photographs around, I was just a teenager taking them to Time and Newsweek, it was a challenge seeing people, but it was different back in the day. But there was one photo editor at the New York Times Sunday Magazine, a great old Irish guy who, for whatever reason, took me under his wing, you know he saw me, an Irish kid from the Bronx, and he really wanted to help me, as a lot of people did for my career. So he published one or two of my photos and calls me up one day and said, "Hey Ken, I have an assignment for you." I said "Excuse me? An assignment? You want to send me someplace?" He said, "Yes, I like your work and I want to help you out." I asked, "What is it?" He said, "I don’t know if you can do it or not because it’s on Thanksgiving Day and you know, you probably have family." I said, "Mike, Christmas, New Years, Easter, Thanksgiving. Give me an assignment, I’ll be there. Forgoing any holidays or special occasion. What’s the job?" He said, "On Thanksgiving Day, they have an annual concert and party afterwards at the Fillmore East." I’m going_, Oh my God. Oh My God. Should I tell him Bill Graham hates me? No, I’m not gonna tell him that._ He told me Jefferson Airplane, Johnny Winter would be there and he’d have a credential waiting for me at the box office when I got there, and if there are any problems, he gave me his phone number to call—only in an emergency. I can’t tell you how excited I was. I got to the box office, there was a credential, it said, Ken Regan, photographer, New York Times Sunday Magazine. I go in and start shooting the first act and maybe three songs into the first act, this familiar voice and hand grabs me by the neck and he said, "Are you gonna bust my balls on Thanksgiving day? Get outta here!" I said, "Mr. Graham, look I got a credential! New York Times Sunday Magazine!" He said, "Who gave you that? I’m gonna fire them!" He dragged me out to the box office and said, "Did you give this guy a credential?" They said, "Yes, he’s with the New York Times. They called." He said, "How do I know your friend didn’t call to get you in?" I said, "Listen, Mr. Graham. Here’s Michael O’Keefe’s number. He’s one of the photo editors at the New York Times Sunday Magazine. Call him." He came back five minutes later and said, "Okay, I spoke to him. Just don’t get in my way." I then proceeded to photograph Johnny Winter, Jefferson Airplane, and down in the basement, decorated beyond belief is this beautiful Thanksgiving dinner, where all the artists came and the whole crew and the bands... and me! And I was able to photograph all this. I processed the film the next day in my bathroom and brought it down to Michael O’Keefe two days later and he said, "This looks great! I’ll call ya." He called me back a week later checking captions and things like that, and I said, "Is this gonna appear, really?" He said, "Well anything could change but I’ll let you know." So within three weeks, the _New York Times Sunday Magazine _did a three page spread with my photographs and my name in bold-type. I ran all over the Bronx with that magazine, showed all my friends, brought it to school with me. It was a big, exciting moment in my life, to be published in a magazine with such presence and character. I made some copies of some of the photographs I really liked, put them together with a copy of the magazine and sent them to Bill Graham with a note, saying "Mr. Graham, I really appreciate this, you can’t imagine what it’s done for me and what it may do for my career. Thank you, thank you, thank you." Months go by. I didn’t hear from the guy. I go, what a prick! He doesn’t even have the courtesy to thank me, I made these prints on my own! I’m at home one night, four months later, doing my homework and my mom comes in, she said, "There’s a phone call for you." I said, "Who is it?" She said, "Well he said his name is Bill Graham. I don’t think it’s the preacher ’cause he sounded really gruff." Knowing who it was, I answered the phone and said, "Mr. Graham, what’s the matter?" He said, "Listen, thank you for sending me the magazine. It looked great. You’re the first photographer on his own to send me photographs. I can’t tell you how nice that was, what a gesture it was on your part. Anytime you wanna come back to the Fillmore East, you call me. Here’s my private number. No matter who the act is, you call me." For the rest of my career, Bill became my surrogate brother and opened up doors to Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones, whoever I wanted to photograph.

Click to subscribe

GQ: Making prints like that, is that an unusual practice in the field?

Ken Regan: Yes. Very. [laughs] I don’t think that people did that and it’s something I did for the rest of my career. Whether it was the Kennedy family or Colin Powell or the Rolling Stones, I always sent a thank you note with photographs.

Rock's Back Pages with Photographer Ken Regan

GQ: Could you tell me about the stories behind them? We have a few of Bob Dylan, particularly in that Rolling Thunder Revue/Renaldo and Clara era. It looks like you spent a lot of time with him. Can you tell me how that came to be?

Ken Regan: Well, again, it came to be because of Bill Graham. I started to work for some of the magazines and Time called me up and said, "We’d like to do a story on Bob Dylan, he’s doing a tour with his band and it’s apparently his last tour with the Band." I said, "I don’t know if I’ll be able to do it, Bob is very private, he had that motorcycle accident, he’s only come back to play again in the last year or two, but I’ll try." I call Bill Graham up, told him Time was interested in doing a story on Bob and the Band, and did he think he could get access for me? He said, "Bob is difficult but let me try." He called me back two weeks later, and said, "I showed Bob some of the photos you did, and he said fine." So Time sent me to Chicago, Bill was there, he introduced me to Keri Weintraub and David Geffen and all these people, I go, my God! This is amazing. Then I meet Bob, who’s nice, and he said he liked my photographs, just don’t get in my way, take all the photos you want of the audience onstage, but none backstage. I said fine. The first night, I was in the wings on the stage, moving around, trying not to get in his eye line and it was a great experience. I always like doing something different, so I like photographing the reaction of the audiences. There was a woman in the second row in her 60s with grey hair and glasses jumping up and down, applauding and clapping, and it was a wonderful photo because she was surrounded by all these young kids. I met Bill the second night and he said, "Bob didn’t say a word so it looks like you’re okay." I said, "Bill I got a question. The woman in the second row, grey hair... she was terrific." He said, "You photographed her? That’s Bob’s mother. Whatever you do, don’t ever release those photos because if you ever want to see Bob again, it won’t happen." The second concert, I photograph her again, and Time ran a spread of the photographs after the concert, and I was thrilled, it was my second big publication in terms of a spread. Like I’ve always done, I made up some prints for Bob and the ones of his mom. Bill said he’d send them along. That was my first experience one-on-one with Bob, I photographed him at Forest Hills when he got booed off the stage. A year goes by, I’m home sleeping and it’s 3 in the morning, and the phone rings and it’s Barry Imhoff who was Bill Graham’s partner. Barry said, "Hey Ken! How are ya! I" said, "Ken! It’s 3 in the morning, I’m sleeping! You people in California don’t realize the time difference." He said, "No, I’m in New York. I wanted to see what you’re doing in the next couple of months." I said, "I don’t know, I’m working for all these magazines. What’s up?" He said, "Well Bill and I are putting together this little tour and were wondering if you were interested in working with us." I said, "Tell me something about it." He said, "Just a second, I wanna put someone on the phone." So this guy gets on the phone and says his name is Louie Kemp, Bob Dylan’s boyhood friend, they grew up in Minnesota, he runs a company called Kemp Fisheries. I’m like, it’s 3am. What is going on here? He said, "I’m co-promoting a tour with Barry and Bill that Bob Dylan’s gonna do." I went speechless. He said, "We’re interested in meeting with you and having you do the entire tour." I said, Mr. Kemp, can I speak to Barry a second? I said, "Barry, if this is a fucking joke, I’m gonna hunt you down and take you apart completely." He said, it’s no joke! There was a pause and someone picks up the phone, and I recognize the voice instantly, it was Bob Dylan. He said, "Ken I’m sorry to wake you this early in the morning, we were rehearsing all day and didn’t realize what time it was. I’ve seen your photographs and by the way, I want to thank you quite a bit for sending me those photos, especially the ones of my mom that you didn’t release, and it gave me a sense of immediate trust with you. We’d like to meet with you. Can you bring your portfolio?" I said, "Now? I’ll come over now!" He said, no, tomorrow was fine. So I went over to S.I.R. where they were rehearsing and met with Bob and Louie and Barry and we chatted for about a half hour and Bob said, I want you to do this tour. This is very unusual because I’ve never done this before. We’ll be on the road for almost three months. Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, David Mansfield, T-Bone Burnett, and a lot of guest appearances from various artists we haven’t reached out to yet. We’re doing a film called Renaldo and Clara, which I’m directing, and I want you to photograph everything that happens 24/7. You’ll have complete access. No one will be allowed to take any photographs but you. He said, "We’ll start rehearsals in a week, we open Halloween Night in Plymouth, Massachusetts and we finish at Madison Square Garden in mid-December." In that period of time, Sean, I took 13,750 photographs. Every night, Bob and I after the show or a party would sit down and he would go through all the contact sheets and when we were finished, we’d have to project the color, and he’d say yay-nay. We had no signed contract, this was just a handshake. That’s what we did every single day. He approved some, others he didn’t, he’d kill them or save them, but they were definitely out. As the tour started, it got great interest, I was getting calls from People, Time, Rolling Stone, and I told Bob I was getting all these inquiries. He said, I figured that would happen. You pick what you want for each of the magazines, run them by me, and we’ll give them each something exclusive. And that was a big breakthrough for me in magazines, because it was an exclusive with Bob Dylan and it opened a lot of doors.

**GQ: ** They’re just not shots you typically see of Bob.

Ken Regan: It started a relationship with Bob and I that lasted for almost 30 years.

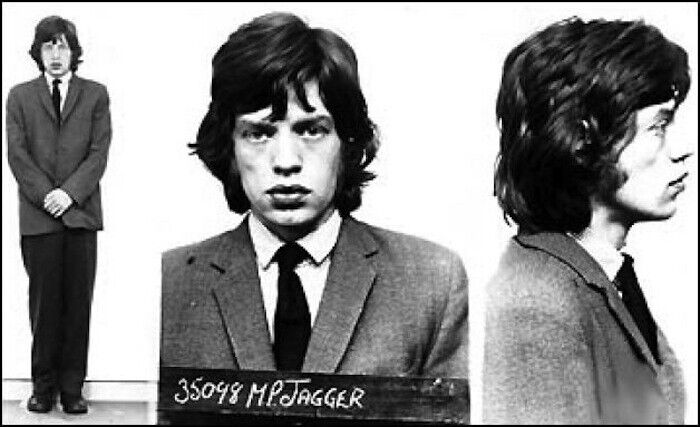

GQ: Tell me about spending time with Mick Jagger. I’m looking at a shot of him with Andy Warhol.

Ken Regan: That was at the Factory. I was doing a cover story and an essay on Mick for one of the British publications. He lived in New York in a beautiful townhouse on the west side. We started there and Mick is an avid workout person, he works out every day. His trainer was there, we did a whole series of pictures of him working out, running on Riverside Park, and he said, "Let’s walk through the city." We went all over the place. Every time I saw something I thought might be a good photo, we stopped and it was great. He’s great, very cooperative. He said, "Hey! Wanna go to Warhol’s?" And we went down to the Factory, Andy was there, and they were kidding around with the camera, and we took some photographs. It was unusual, and one of my last big shoots with Bob Dylan was to be for a cover of Time in 2001, I had been in Anguilla, I was flying all night long, got to the city, met my assistant, went out to Telluride—I was flying for 18 hours. I got to the hotel at about 11 o’clock, got a room, went to sleep. There’s a knock on the door and it’s 12. I go to the door and it’s Bob. He said, "I’m so glad you could make it and do this cover. This is the town where Butch and Sundance hung out. They got a bar here. Do you want to walk around for a while?" I said sure. I grabbed a couple cameras, go to the lobby, Bob’s waiting, and we walked along the town. We did photographs. People were coming out of the stores, asking if Eric Clapton was going to be there, Bob said, "I don’t know!"

We went to the bars, and then to a cemetery. There’s a picture of Bob sitting in this old cemetery with a dog, he used to pick up dogs all the time, he had a fondness for animals. It’s a wonderful photograph. We go to the concert that night, and he was shaking hands with people, very not Bob Dylan. He said, "Listen right after the show, I want you to come ride with me in my camper to Arizona." I said, "Great." Thinking, I’m still not gonna get any sleep. But we had to meet at the trailer right after the encore. One of his assistants at the trailer said, "Hey! Bob needs you backstage. I don’t know what’s up but he’s told everyone to find you."

So I go backstage, he said well, we have a surprise guest. Norman Schwarzkopf. He said, "Norman Schwarzkopf was in the audience and asked to come meet with me." I’ve done a number of wars and this was an unlikely pair. He had his assistant get a white hat for him, and Schwarzkopf comes back, and there’s pro-war and anti-war, and he came to Bob and said, ’I’ve been a fan of yours for 25 years and the most prolific song written in the 20th century was ’The Times They Are A-Changin’.’ We took all these photographs, none of which have ever been seen.

GQ: How much are you shooting these days?

Ken Regan: In the mid ’90s, the whole change was starting to happen, not just technically, but photojournalism, which I pride myself on being a photojournalist, I’ve done a lot of work on wars, riots, politics, etc. I saw it coming to an end in the mid ’90s, because magazines didn’t have to send... it was maybe 12, 15 of us... who they could send to Russia, the Middle East, Columbia, on assignment. Costly, but they knew they’d get what they wanted. Once digital happened, they could hire people in different parts of the world. And because it was digital, they could correct in Photoshop. So I tried many different things, my career is very diversified. I thought, I won’t be able to make a living at this, so I did ad work and corporate work in film and television. My big plus in film was Jonathan Demme. We hit it off, I’ve done every one of his films since Married to the Mob, with the exception of Rachel Getting Married.

GQ: Do you miss it?

Ken Regan: I did eleven Winter and Summer Olympics. Every time I turn on the television and see a demonstration on the Brooklyn Bridge or Egypt, it just tears my heart out. The Rolling Thunder tour is my most memorable shoot. It was a first and I don’t think you ever saw that happen again and you never will. I don’t know if you know this but I did a book with Sam Shepard, who was also on tour with us, that came out a year after the tour was over. The tour started with many different factions to it, Bob wanted to do a film. He hired Marlon Brando to direct it and Sam to write the screenplay. Things didn’t work out between Bob and Marlon, so he directed the film himself and Sam wrote the screenplay. The film turned out to be Renaldo and Clara, which, when it was released, was five hours. Bob wanted seven hours. Sam and I hit it off and became friends and he called me up and said, since I proposed to do a big coffee table book because of the access I knew I was going to have, and I talked to Sam about writing the text, and Random House pulled the plug at the end of the day because it was going to be too expensive to do. So we found another publishing company and did a smaller version, which we didn’t like a lot, the paper in reproduction was like toilet paper. I’ve worked with him on a number of films, on A Fair Game most recently, it was 2004. I had never done an exhibit before and I’d been asked and asked and asked. I’m a private person so I’ve never had any desire to do anything but work. People kept pushing me.

We get a call from a small publishing company and they wanted to re-release the book on Rolling Thunder. I said, "Jesus, it looks so bad why would you want to do that?" And they said it was selling for 0 on eBay. I said, you’re kidding! We did the revised version of the book and T-Bone Burnett wrote the afterword. This gallery heard about the book said, you’ve got all these pictures of Dylan and the book coming out, why don’t you do an exhibition? I asked Sam if he’d come up for the opening, and he said he would but he wouldn’t sign any books.

I’ll tell you one more quick story. I don’t know if you ever saw the live album of Rolling Thunder. There’s a picture of Bob on the cover with the hat and scarf. Well, when were going through all the images every single night, we came across this picture and there was a front shot and two profiles, split second it happened in the dressing room. Three or four nights later, Bob looked at this photograph and said, "Ken, this is the best picture ever taken of me. I really mean that." I said, "Well gee, thanks Bob."

For 25 years, I always ran photos by Jeff Rosen, who represented Bob. I can’t tell you how many times I tried to have this picture used for everything from being honored at the Kennedy center to the Academy Awards, it was always no. He wanted to save it. Finally, I said to Jeff Rosen, what do you want to save it for, his obit? A couple years later, Jeff called me up and said Bob wanted to use the photograph on the live album from Rolling Thunder

If you've been around longer than me, perhaps you were already familiar with Ken Regan's photography.

I'll admit: I didn't discover him until just the other day, under somber circumstances. A colleague forwarded this obituary in Rolling Stone, advising simply: "He's a big deal." The music photographer died of cancer one week ago.

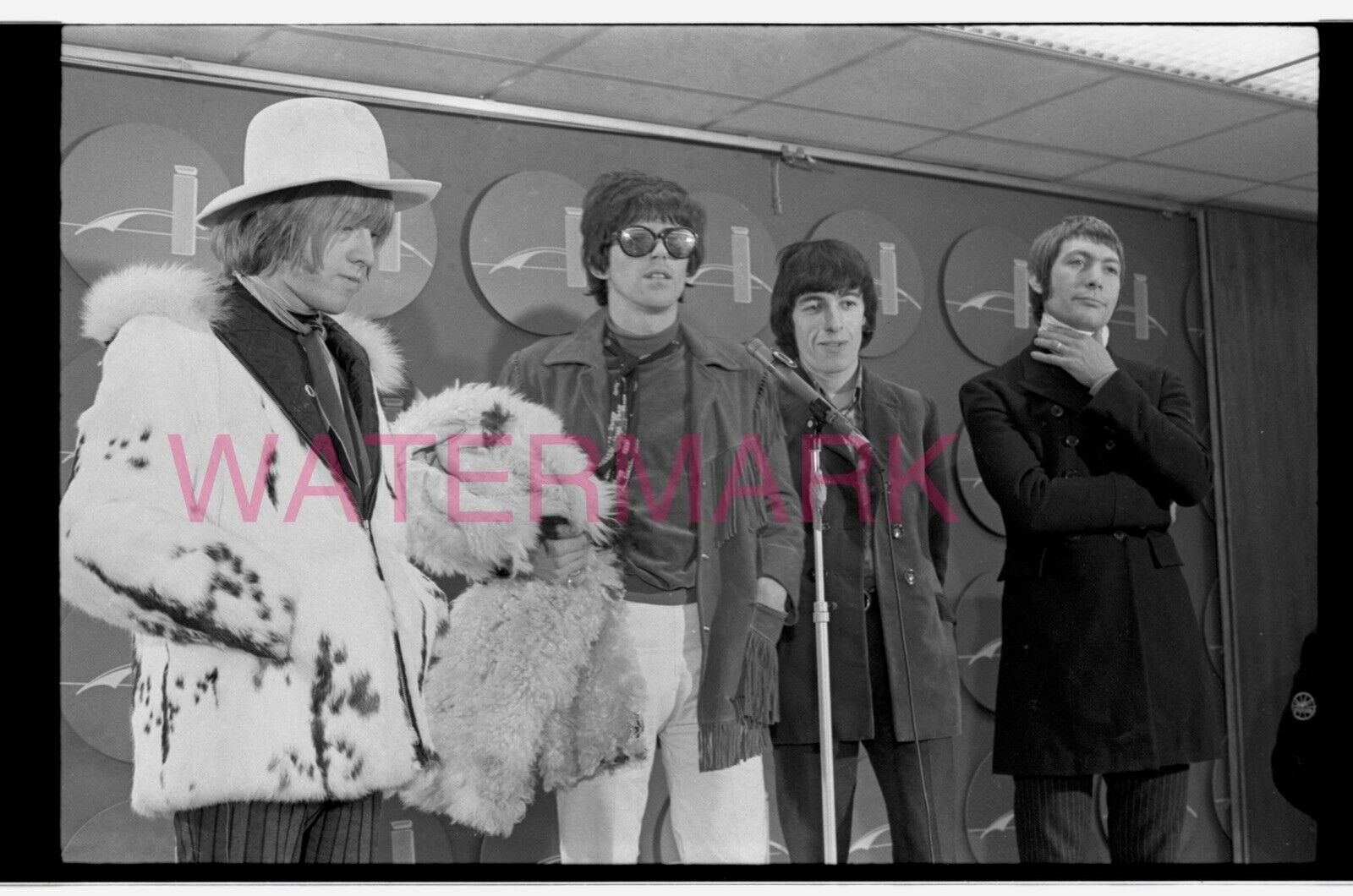

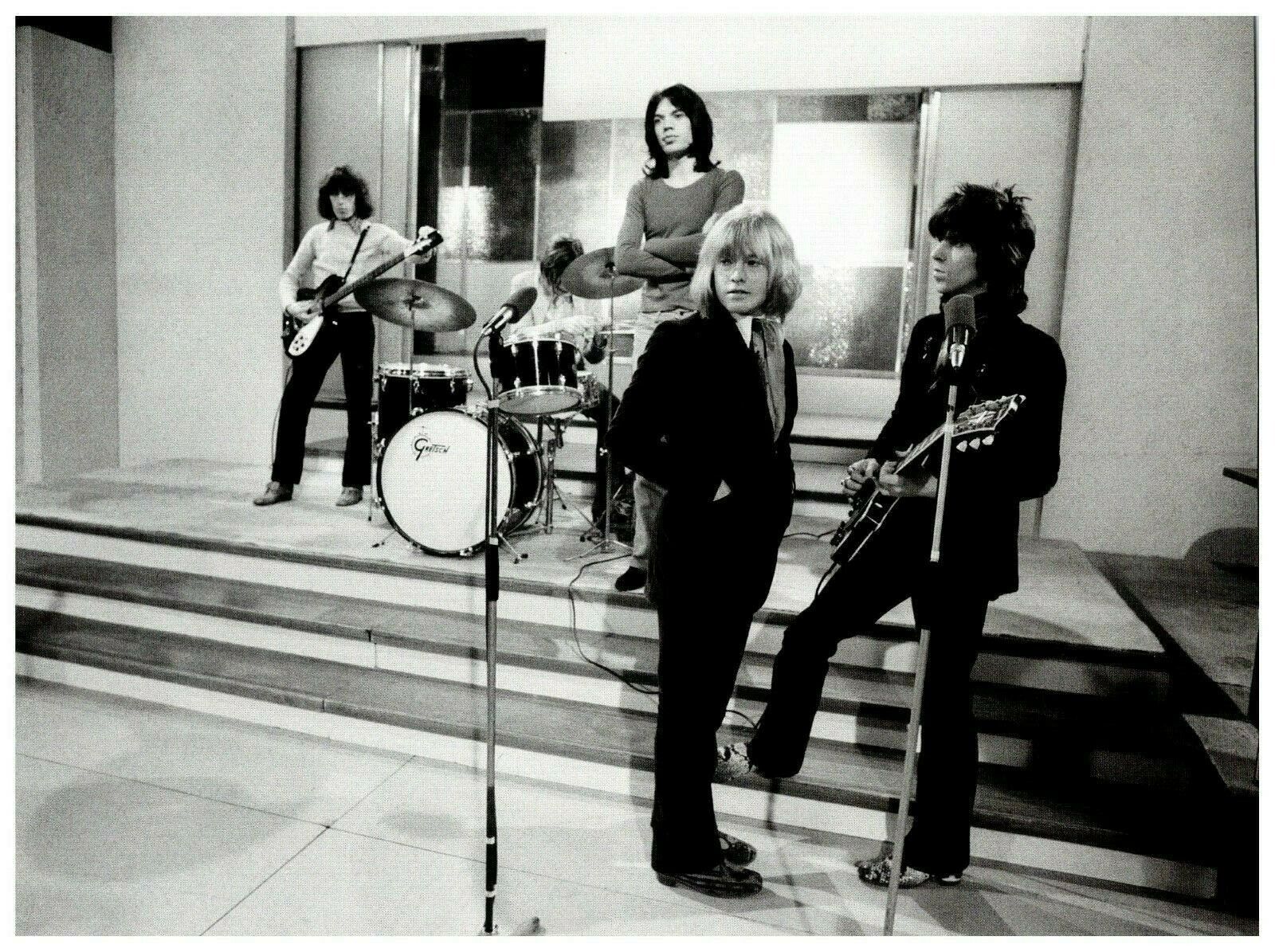

Photographer Ken Regan with the Rolling Stones, 1977

Courtesy of Ken Regan/Camera 5

All Access

The Rock 'n' Roll Photography of Ken Regan

by Ken Regan, Jim Jerome, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger and James Taylor

Hardcover, 288 pages purchase

So I got a hold of his book, All Access, which was published one year ago this month; and after only a few minutes with his photos, I was enamored. I pored over his first-person anecdotes: Stories of his first important shoot — with Elvis Presley, who had just returned from Army service in Germany; of catching Leonard Bernstein plugging his ears at a Beatles concert; of accidentally drinking hallucinogenic punch backstage at a Rolling Stones concert; of his exclusive access to one of Bob Dylan's tours.

Granted, there's no shortage of Rolling Stones photos in the world. But how often does Mick Jagger write personal book introductions for photographers?

"As Ken would accompany us on our tours, it just so happened that I would end up accompanying him on his gigs as well," Jagger writes.

Regan's reputation was such that, with his kind of access, even the Rolling Stones would call on him for favors.

Article continues after sponsor message

There's too much to say and too little space here, so I'll leave you with Regan's photos, captioned in his own words from the book.

I didn't know him personally, and regret that I missed the chance to ask him about his experiences. But the beautiful thing about being a photographer is that you're not just a witness to your time, but you also leave behind a visual legacy of your life.

Photographer Ken Regan, best known for his iconic images of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen and Jimi Hendrix, died of cancer on November 25th, Rolling Stone has confirmed. A spokesperson for his studio declined to give Regan’s age, calling him “ageless.”

A native of the Bronx, New York, Regan logged countless hours on the road with rock stars, shooting the Beatles on their 1965 tour, Hendrix at the Fillmore East in 1968, Springsteen on the Amnesty International tour in 1988 and Neil Young at the Ryman Auditorium in 2005. He also photographed the Concert For Bangladesh in 1971, the Last Waltz in 1976 and Live Aid in 1985. In 1975, Regan toured with the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review, shooting thousands of pictures along the way.

“Many times I’ve been onstage only to see Ken’s beady left eye drilling through me with that wry grin under his camera and know he’s got the shot he was after,” Keith Richards wrote in the preface to Regan’s 2011 book, All Access: the Rock & Roll Photography of Ken Regan. “I know a lot of photographers and they all have a personal style. When I see Ken in front of me, I know what he’s waiting for . . . the moment!“

The Rock & Roll Photography of Ken Regan

Regan had a knack for capturing private scenes offstage: Andy Warhol hanging out with Mick Jagger at the Factory in 1977; Bob Dylan meeting Bruce Springsteen for the first time backstage at a show in 1975; and a shirtless Dylan playing backgammon that same year. One of his Dylan shots was used on the cover of The Bootleg Series Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975; another was featured on the cover of Rolling Stone’s June 21st, 1984 issue.

RELATED

Woodstock 50: Jay Z, The Killers, Dead and Co

Woodstock 50 Details Full Lineup With Jay-Z, Dead & Company, Killers

RS Daily News: ‘Toy Story 4;’ Jack the Ripper Identified; Lil Keed’s ‘Move It’

Regan also spent years covering the sports world, and his Muhammed Ali photographs have been widely reproduced. In 1975, he photographed Ali and George Foreman’s famous Rumble in the Jungle match in Zaire and landed a photo on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

More recently, Regan had turned his attention to documenting film shoots. He worked with Clint Eastwood on the Bridges of Madison County, Jonathan Demme on Silence of the Lambs and Alana Pakula on The Pelican Brief.

Regan continued to work until he was sidelined by illness earlier this year.